Ddaq100

Return to main navigation:* Main page

DISABILITY DISCRIMINATION AWARENESS QUESTIONNAIRE (DDAQ) DRAFT EARLY FINDINGS (n=100)

Disability discrimination is common in the UK including the NHS. (Tyerman, 2023). This is not surprising as neither the disability requirements of the UK Equality Act (EqA, 2010), nor the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD, 2006) are covered adequately in professional training. Yet, healthcare staff have specific additional duties, expected for example to ‘understand equality legislation and apply it to their practice’ (HCPC Standards of Proficiency, para 5.2). In response, resources have been developed to raise awareness, promote good practice and reduce discrimination. This includes a Disability Discrimination Awareness Questionnaire (DDAQ); 5 X Disability Discrimination Practice Checklists (DDPCs); background, suggested action and reference material. These are hosted on a specific website: https://equitynotjustequality.co.uk/

A starting point is the DDAQ (Tyerman et. Al. 2023). This focuses on UNCRPD and Equality Act objectives, rather than legal liability. Items are taken from the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) statutory codes on ‘services, public functions and associations’ (EHRC, 2011b) and ‘employment’ (EHRC, 2011a) and technical guidance on further and higher education (EHRC, 2014). They cover the definition of disability (7 items) and forms of discrimination: direct (3), indirect (4), arising from disability (2), reasonable adjustments (10), harassment/victimisation (2) and other unlawful behaviour (2). Invitations were made via teaching presentations, articles and personal, group and service contacts.

Respondents

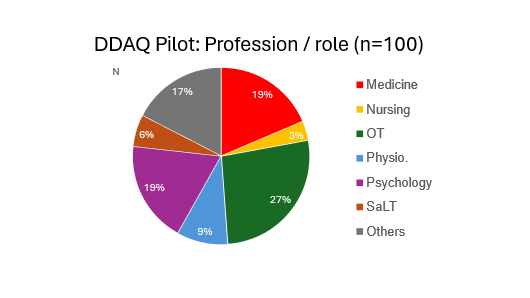

Responses are reported below for the first 100 healthcare staff, of whom 88% were qualified professionals including OTs (26%), psychologists (19%), medical practitioners (19%), physiotherapists (9%) speech & language therapists (6%) and nurses (3%), as llustrated below. The ‘Others’ include other therapy, administrative and assistant staff

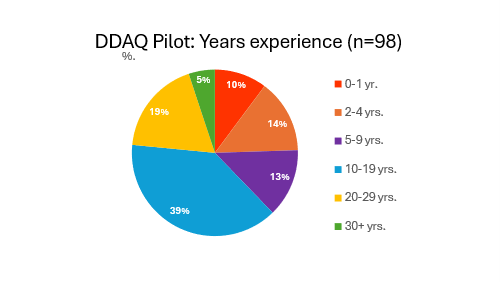

As illustrated in the Figure below, this is an experienced staff group: 24% > 20 yrs.; 63% > 10 yrs. and 76% > 5 yrs. Only 24% have less than 5 yrs. experience.

Of 88 asked in an added question, 39% reported one or more reasons to have sought information about disability discrimination. This most commonly involved the experience of clients/patients but also their own experience/observations, those of family/friends and colleagues. Whilst 50% of 66 responding individually to the DDAQ reported a prior reason, only 21% of a neurorehabilitation team who responded as a service did so. As such, the influence of past relevant experience needs to be explored in a large representative group.

DDAQ scores

The mean DDAQ score was 17.76 (median 17.5, range 1-30), equivalent to just 59% overall awareness. In order to prevent disability discrimination you would wish health professionals to know all except perhaps two items (Q12 & Q16) related to the legal justification for not making adjustments, If you allow one other gap, the provisional target score is 27-30 (i.e. 90% awareness or higher).

As illustrated in the figure below, the target score of 27-30 was achieved by just 11% of respondents, with 38% scoring 50% or less and 13% scoring 33% or less. Scores are well spread with a relatively flat and wide peak across scores 11-22. Whilst those with more experience might be expected to have more awareness no significant relationship with years of practice was found (Spearman’s rho =0.17, n.s.).

Awareness on individual DDAQ items ranged from 23% to a high of 97%, with 10/30 items known by under 50% of staff including 3/7 items on the definition of disability and 3/10 on the duty to make reasonable adjustments (RAs). At least one item was known by less than 50% in each section except for Direct Discrimination – see below.

| Summary of key items of concern with <50% awareness | Aware | |

| 4 | Exceptions to core disability definition for people with cancer, HIV infection & MS | 23% |

| 5 | A medically diagnosed cause of impairment is not required | 25% |

| 6 | Need to set aside treatment & adjustments in judging if disability covered by EqA | 46% |

| 13 | Indirect discrimination unlawful, even if disadvantage not intentional or even realised | 49% |

| 21 | Need for risk assessment if denying work/service adjustments on grounds of H&S | 39% |

| 23 | If co-operation of others needed, obstructive/unhelpful behaviour to be dealt with | 37% |

| 25 | A reasonable step has not been taken if adjustment does not reduce disadvantage | 46% |

| 28 | Disability related victimisation – definition and the nature of ‘protected acts’ | 31% |

Other items of particular concern include the anticipatory nature of the duty to make RAs for providers (54%) and the requirement not to take a lesser step if a RA could reduce disadvantage (60%). Whilst there are many ‘partly aware’ responses to some items (mean 28.6%, range 3-50%), these would likely not prevent inadvertent acts of discrimination.

Awareness self-ratings (n=100)

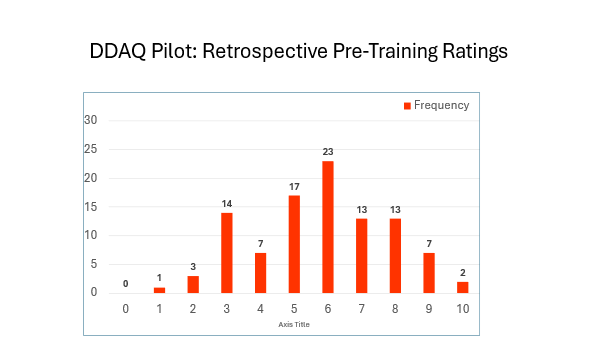

Respondents provided three self-ratings: (1) awareness before training, (2) retrospect ratings of prior awareness after DDAQ completion and (3) current awareness after the DDAQ training. The range, median, mean & change in self-ratings were as follows:

| Mean awareness self-ratings | Range | Median | Mean | Change | |

| 1 | Pre completion self-rating prior to training | 2-10 | 6 | 6.26 | - |

| 2 | Retrospective pre-completion rating post-DDAQ | 1-10 | 6 | 5.78 | - 0.48 |

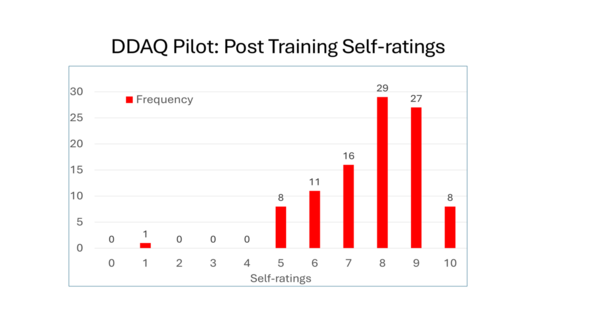

| 3 | Post-completion current self-rating after training | 1-10 | 8 | 7.74 | +1.96 |

The 0.48 mean fall in self-ratings of prior awareness after completing DDAQ indicates that staff overestimated their awareness to a modest degree prior to training (t=2.79, p<0.006).

As a result of the training, mean awareness self-ratings rose significantly by 1.96, showing the benefit of the DDAQ (t = 12.05, p<0.0001). This represents a 34% increase in overall awareness.

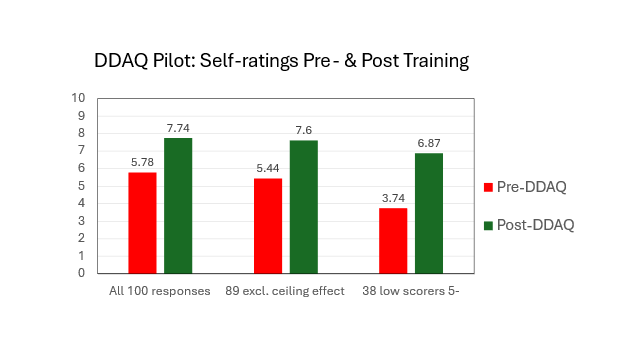

The increase in awareness is illustrated below in the distribution of self-ratings for retrospective pre-DDAQ completion and post-DDAQ training.

On comparing the distributions, the overall increase is likely reduced slightly as two respondents retrospective rated their pre-DDAQ awareness as 10/10 and 7 others as 9/10. Both the two scoring 10 and 4/7 scoring 9 also achieved the DDAQ target score of 27-30. These 9 did not have the same need or the scope to increase by the mean rise of 2.16 points for the other 91 respondents. This likely represents a ceiling effect for these 9 respondents. The mean increase of 2.16 (5.44>7.6) for the 91 staff in need of greater awareness (i.e. score 8 or below) represents a 40% increase, up from 34% for all 100.

The increased awareness is marked for low scorers. Those with a rating of 5 or below fell from 42% to 9% and those rating 4 or below fell from 25% to just 1%. The mean rises of 3.07 for the 42% scoring 5 or below and 3.36 for 25% scoring 4 and below represent increases over pre-DDAQ training ratings of 80% and 109% respectively. Given the marked increase for lower scorers, mean ratings for such staff are included below, along with all 100 respondents and the 91 without the likely ceiling effect for 9 respondents

The first 100 DDAQ responses from mainly well experienced health professionals, most of whom work routinely with people with disability, confirm a striking lack of awareness of the specific disability rights and discrimination. The overall DDAQ target score was achieved by just 11% of staff, with 38% scoring 50% or less.

Of the 30 individual items, 10 were known by under 50% of staff. Whilst this includes at least one item in each section of the DDAQ except direct discrimination, it is of particular concern that this includes 3/7 items on the EqA definition of disability and 3/10 items on the duty to make reasonable adjustments. As such, NHS staff and Trusts are at risk of inadvertent acts of discrimination in clinical practice and service delivery. This is in the context of the UNCRPD’s additional responsibilities for healthcare staff, over and above the core requirements of the Equality Act and Public Sector Equality Duty.

Completing the 15-20 min. DDAQ training resulted in a 34% increase in self-ratings of awareness for all respondents, 40% if the 9 highest scorers with no need and little scope to improve are excluded. For those with previous self-ratings at or below 50% and 40% rose by 80% and 109% respectively. The extent of the rise in awareness indicates a lack of effective training on the disability requirements of the UNCRPD and Equality Act.

Results from this pilot suggest that the DDAQ training exercise significantly improves awareness of disability discrimination. The DDAQ and other resources (including the 5 Disability Discrimination Practice Checklists) are available to NHS staff now at no charge. There is a need for the DDAQ to be completed by a large group of representative staff to check for any differences across professions, experience and work settings and consider more targeted training. This would need commitment from one or more NHS Trusts.

Whilst the DDAQ was developed initially with the NHS in mind, it seems likely that it has much wider potential public and private sector application. This warrants exploration. Any interested individuals, teams, services or organisations are invited to make contact.

In conclusion, there is an urgent need to review training on disability rights and the specific responsibilities of health professionals under the UNCRPD and the Equality Act. Given the difficulty in engaging NHS staff in post in the DDAQ training, this could potentially be achieved by including the DDAQ in Trust induction programmes or on internal promotion to a service or staff management role. We would then be in a much stronger position to respond to the call for urgent action to advance health equity for persons with disabilities from the WHO (2022) and the UK Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC, 2017).

References

EHRC (2011a). Equality Act 2010 Employment Statutory Code of Practice. Equality and Human Rights Commission. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/employercode.pdf

EHRC (2011b). Equality Act 2010: Services, public functions and associations. Statutory Code of Practice. Equality & Human Rights Commission. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/servicescode_0.pdf

EHRC (2014a). Equality Act 2010: Technical Guidance on Further & Higher Education. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/equalityact2010-technicalguidance-feandhe-2015.pdf

Tyerman A (2023). The WHO call for urgent action to advance health equity, set in the context of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Equality Act. Clinical Psychology Forum, 368: 33-42. Leicester: British Psychological Society. Download ‘CPF_368_ Andy Tyerman (pdf)’ at the bottom of web page: https://equitynotjustequality.co.uk/context United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006). UN General Assembly Reports on Social Development. https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd